Endings: of English independence, of the Viking Age

English politics during the eleventh century was a mess, further unbalanced by Norse intrigues on two fronts: in the Danelaw and across the English Channel

in Normandy. In summer 1013, Sweyn Forkbeard, the King of Denmark, had conquered England and was in the process of being confirmed king when he suddenly died

in February 1014. The witan decided to recall the former king, Eţelred, who had fled abroad, and made him promise to rule more kindly, but both he and Sweyn's

young son, Cnut (Knútr, but usually called Canute in English history), whom the Danes had proclaimed king, wound up betraying and harrying in the Danelaw in

the process of the Danes' withdrawing and Eţelred's reclaiming control. In 1015 Cnut returned with assistance from Jarl Eric of Norway (Eiríkr Hákonarson), who

was married to his sister and was then at the apogee of his power - and almost certainly also with forces from the east and from Sweden, as a result of

alliances from Sweyn's two marriages - and was joined immediately by Thorkell the Tall, a powerful follower of Eţelred's whose brother had fallen foul of one

of the king's actions. The king's son Edmund Ironside had formed alliances in the Danelaw - against his father's wishes - and Edmund's and Cnut's forces fought

their way up and down and round about England until Eţelred died in April 1016. The witan gave in and chose Cnut as king; the populace rallied around Edmund.

There was continuing treachery and side-switching. In October, Cnut beat Edmund at the Battle of Assandun (either Ashingdon or Ashdon, both in Essex) and they

agreed to split England at the Thames - which gave Cnut the vast majority of the country - with the proviso that whichever of the co-kings survived the other

would become sole king of the entire country. Whereupon Edmund Ironsides died on November 30, whether from his wounds or further treachery. Cnut was crowned

king at Xmas and the nobles swore fealty early in 1017. In July that year he married Eţelred's widow, Emma of Normandy, gaining the Normans' support even though

Eţelred's sons Edward (the Confessor) and Alfred (Ćţeling) were being sheltered there by their relatives.

Cnut's older brother Harald had become king of Denmark, but he died in 1018 and Cnut returned to Denmark to claim the throne, taking with him his young son

Harthacnut. He set up Jarl Ulf, who was married to his sister, as regent and left the boy there in his guardianship to be raised Danish. Jarl Ulf managed to

retain control of Denmark against attacks from the allies King Anund of Sweden and Olaf Haraldsson (the Fat - later "St. Olaf") of Norway and grumbling from

the freemen about the king's being always in England, but in order to do so he double-crossed Cnut by having the Danes acclaim the boy Harthacnut as their

king, which in effect meant he was, as his guardian. In 1026 Cnut returned and with Ulf's help trounced the Swedish and Norwegian kings at the Battle of the

Helgeĺ. He and Ulf had a great argument that Xmas Eve while playing chess in Roskilde, and next day, Xmas Day, one of Cnut's housecarls (personal followers)

killed the jarl in Trinity Church, the forerunner of Roskilde Cathedral, on the king's orders.

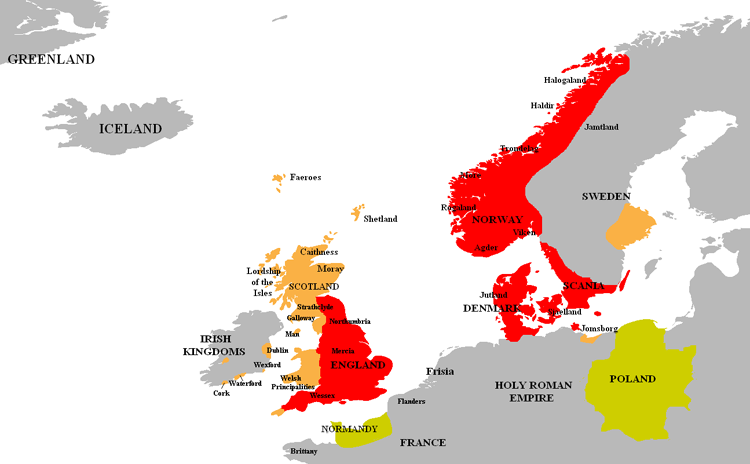

Cnut was now ruler of a "North Sea Empire" that united England, Denmark, Norway, and part of Sweden (Anund apparently retreated to a remote area), although

after the death in turn of Earl Hĺkon, whom he had re-established in control of Norway as his regent, and of King Olaf at Stiklastad, he had a hard time

keeping Norway in line using his daughter Ćlfgifu by his first wife (and continued concubine) and her son Sveinn Alfífuson; Magnus the Good ultimately won

control there. Although Cnut was able to secure tribute from rulers in Scotland and Ireland, and to hobnob with the Holy Roman Emperor - and just before his

death win back Slesvig for Denmark by arranging a marriage between his daughter and the Emperor's son Henry - when he died in 1035, his son Harthacnut succeeded

him in Denmark but because he was too busy fending off Magnus of Norway, was not able to get back England until 1040 - when Harold Harefoot, Cnut's own son by

Ćlfgifu, died. Harthacnut's mother and Cnut's legal wife, Emma, had had to flee to Belgium during Harold's reign.

Resented even in England, where his division of the kingdom into four great administrative jarldoms, of which he kept Wessex as his personal domain, was one

step closer to feudalism and where the church was scandalized by his bigamy and encouragement of skaldic poetry praising him in heathen terms, Cnut the Great

was nonetheless an effective and wise ruler whose local empire was a pause of relative calm in a chaotic century.

England continued to prove this. Harthacnut had been preparing a Danish fleet to invade England when King Harold Harefoot died; after he assumed the throne he

had Harold's body exhumed from Westminster Abbey, beheaded, and thrown into a marsh beside the Thames. His supporters subsequently rescued it and reinterred it

in St. Clement Danes. Harthacnut over-taxed England to pay for his continuing military problems in Scandinavia and according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

"never accomplished anything kingly for as long as he ruled." He died suddenly in 1040 and his designated heir, Eţelred's son by Emma, became King Edward ("the

Confessor"). Magnus got Denmark. Edward the Confessor was reputedly extremely pious - he was canonized in 1161 - and was welcomed with joy when he succeeded to

the throne (although his mother Emma supported another candidate and Edward had her imprisoned on a trumped-up charge of adultery with a bishop, which rather

spoils the impression), but the three great earls left over from Cnut's system were out of control and Edward infuriated them and others by constantly

preferring Normans he had made connections with during his exile under Cnut. In particular he was married to Edith, the daughter of Earl Godwin (already a

power to be reckoned with when Eţelred and Sweyn were still struggling, married to Jarl Ulf's sister, and involved in all the kingmaking decisions since

Eţelred's death), yet he passed over Godwin's choice for Archbishop of Canterbury in favor of a Norman. When the townsfolk of Dover staged a bloody riot against

Eustace, count of Boulogne, Godwin refused to punish them and the king exiled him and his family and stuck the queen in a nunnery. The next year, 1052, Godwin

returned with an army and forced Edward to restore his title and send away his Norman advisors. Godwin died in 1053, but his son Harold accumulated even

greater territories for the Godwins, who wound up in 1057 holding every earldom except Mercia. Harold destroyed Gruffydd ap Llywelyn of Gwynedd, who had

conquered all of Wales but was killed by his own men after Harold defeated him in 1063, negotiated with the Northumbrians, and in general acted like an

independent ruler.

Edward the Confessor had no children and had designated as his heir Edward Ćţeling, one of Edmund Ironside's two young sons who had been ordered killed by Cnut

in 1016 but were instead spirited away to Hungary. The discovery that Edward was alive and in the custody of the Holy Roman Emperor was a relief because he was

indisputably in the West Saxon line; the witan accepted him; but when he eventually returned in 1057 (he had been raised as a prince and had married a German

princess and is also known as Edward the Exile), he died within 2 days without being allowed to see the king. When Edward died on January 5, 1066, it was a

foregone conclusion that Harold, who had become ever more politically powerful, would succeed him. The witan chose him and Edward was said to have designated

him on his deathbed.

However, in 1064, Harold had been shipwrecked at Ponthieu, on the coast of Normandy, and brought to Duke William. He accompanied him on a military expedition

against Conan, Duke of Brittany. William claimed that Harold swore vassalage to him. The Bayeux Tapestry, which was embroidered by Norman ladies as a work of

propaganda, shows him making an oath while standing resting his hands on a chest containing the bones of saints. There may even have been such a chest, its

nature concealed from Harold, and he may have been induced to make vague promises. In any event, William claimed that Harold had promised to help him become

king of England; the Normans also claimed that the purpose of Harold's journey had been to bring William word that Edward the Confessor had designated William

his heir. One reason that William was so intent on England was ambition born of insecurity: William the Bastard was illegitimate and although the designated

successor of his father Duke Robert I, had been constantly mocked for it and after he succeeded at age 7, had lost 3 guardians in succession. Another was that

the Pope had had enough of the independent ways of the English church, in both theology and politics, and was backing him with money and moral support.

Harold had trouble consolidating his power in the North. In 1065, the Northumbrians had rebelled against his brother Tostig, who had doubled their taxes.

Harold supported the rebels and gave the earldom to Morcar, then soon after becoming king, cast aside his longtime Danish wife and married the sister of Morcar

and of Edwin, Earl of Mercia - and widow of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn. But by thus increasing his legitimacy, he looked anti-English and he split his own family.

William declared his intention to invade as soon as he heard of Harold's coronation. The Normans started building 700 ships. Harold mustered the English fyrd

(the popular army the king of England could call on in times of need) on the Isle of Wight, but William's fleet remained in port all summer, claiming the winds

were unfavorable. On September 8, running out of provisions, Harold disbanded his troops.

The same day (it is hard not to imagine collusion was involved), Harold Hardrada landed at the mouth of the Tyne with about 15,000 men. Harald also believed he

had a claim to England, but recognized it as weak: it involved understanding the agreement between Magnus the Good of Norway and Harthacnut that when either

died, the other would inherit all his lands and titles as extending to England, although Magnus had never made any such claim. Harold's brother Tostig had

talked him into invading, saying he could get all the nobles of England to support him. On September 20 he defeated the first English force he encountered at

the Battle of Fulford, two miles south of York. Believing Tostig, Harald had only half his forces with him and they were carrying light weapons and wearing

only light armor. But on September 25, Harold met him with a far larger force, heavily armed and armoured, at Stamford Bridge. For a while one of Harald's men

held one side of the bridge, but when he fell, the English forces easily defeated Harald's. Harald was killed by an arrow to the throat, and fewer than 25 of

the 300 longboats were needed to take the survivors back to Norway.

According to Snorri Sturluson among others, before the battle a lone man rode up to Harald Hardrada and Tostig and offered Tostig his earldom back if he would

turn on Harald Hardrada. When Tostig asked what his brother Harold would be willing to give Harald Hardrada for his trouble, the rider replied, "six feet of

ground or as much more as he needs, as he is taller than most men." Harald, impressed, asked Tostig who that had been - and Tostig said it had been the king

himself.

Harald Hardrada was a great viking, and with his defeat and death, the Viking Age is generally agreed to have ended. It was no longer fully worth it to go

raiding; the kings and the national armies had become too strong and brave. After all, most of them, like Harold, were now wholly or partly of Norse stock

themselves.

Meanwhile, having reassembled the fyrd and marched it to Yorkshire at high speed to deal with Harald, and having been in the midst of clean-up in the North,

Harold had to force-march his men all the way to the south coast to deal with William. The wind changed on September 27. The fleet could have been crippled

in mid-Channel, when the slower transports became separated overnight from William's flagship, but the English Navy had laid up its ships in port. William

landed at Pevensey, made an initial base at the Roman fort there, then moved to more solid ground at Hastings and started constructing an earth and timber

castle. Harold moved faster than any other medieval army, taking at most 13 days to get down to London, amass what men were able to reach him, probably at

most 7,000 including his own housecarles, and get to Hastings to take on a force that was probably smaller, but fresh and consisting of picked, well trained

men. William was informed by his scouts of Harold's approach on October 13; at first light on October 14 his forces moved out and they engaged the English

before they could get into position. The Normans all had sophisticated training in horsemanship, although they were rather lightly armed for the axes and

stones the English rained on them, and they at least three times feinted retreat to draw the English out. Harold's brothers Gyrth and Leofwine had already

fallen when Harold was killed, probably by an arrow loosed at random into the English center.

William the Conqueror and the rest of the Normans had long been "Northmen" in name and ancestry alone. The Norman Conquest meant an end to most of the

Germanicness of England. The English would now be forced to pay all the taxes Rome wished to impose and to have only authorized bishops who would make the

long journey to be officially invested by the Pope, and the originality of the English church came to an end. A new Norman aristocracy was imposed, and when

the North rebelled, it was harried with great savagery. The English had to deal with a new language, Norman French, and their clergy would now read and write

only in Latin, as on the Continent; England became an outpost of Europe rather than a center of intellectual ferment, and eventually the new blended language

of Middle English emerged.

Map created by Briangotts, Wikimedia Commons

Cnut's "North Sea Empire"

[1. Cnut's "North Sea Empire" map image from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Canute.PNG]

|