Norway

The push to unify Norway under the control of a single king coincided with the pressure to convert to Xianity. The king generally credited with unifying

the country, although modern historians believe he actually ruled only the southern part, is King Harald Fairhair (Haraldr Hárfagri), (d. 930). Starting in

866, Harald accomplished a series of conquests over rival petty kingdoms, including Värmland in Sweden and modern southeastern Norway, which had sworn

allegiance to the Swedish king Erik Eymundsson. In 872, after a great victory at Hafrsfjord near Stavanger, he found himself king over the whole country.

Until King Olav IV, who died in 1387, every following king claimed descent from Harald Fairhair.

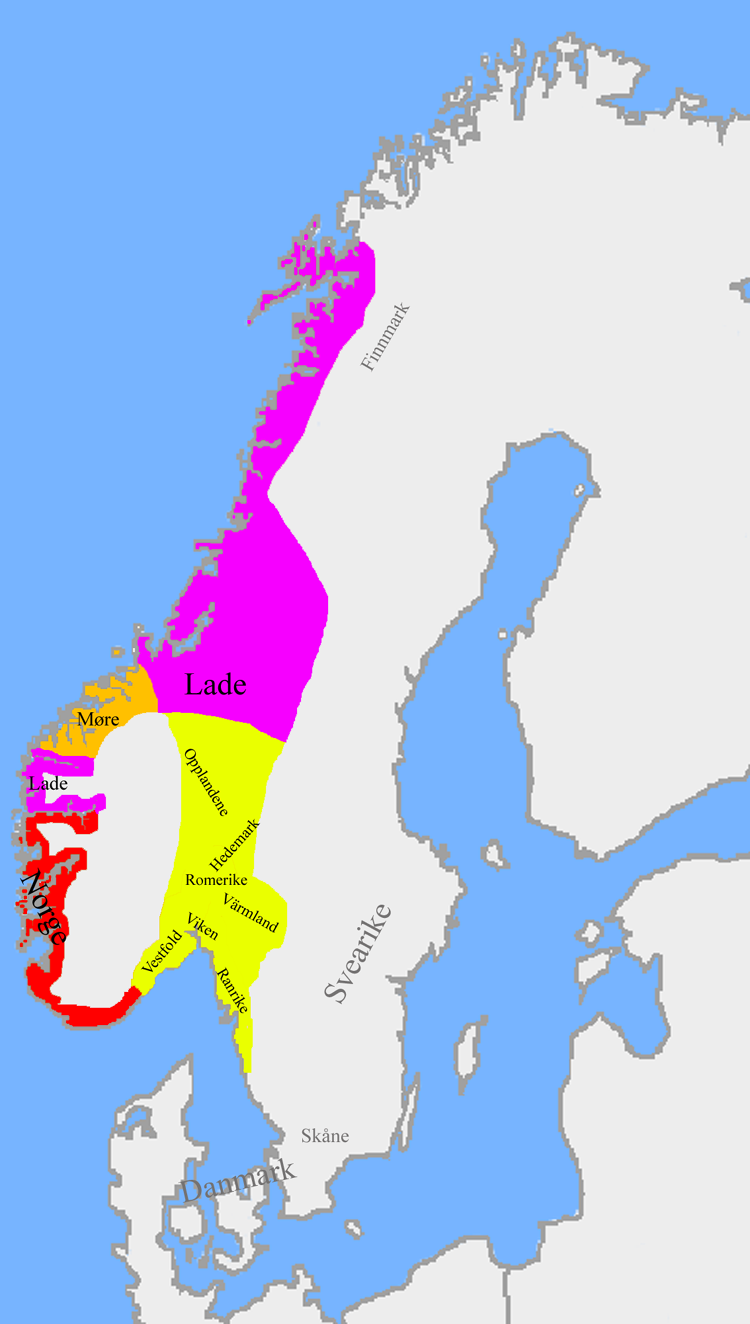

Map created by Tokle, Wikimedia Commons

The kingdom Harald inherited, of the kingdom prior to Hafrsfjord, and of the kingdom under Olaf II (St. Olaf).

Resentment was stirred not just by the conquests themselves, but also by the king's imposition of efficient taxation over all his lands.

In addition, Harald had a large number of sons (between 11 and 20 depending on the source one reads), and strife between them continued after his death,

even though he gave them all the royal title and assigned them lands to govern as his representatives. When he reached the advanced age of 80, Harald handed

over the supreme power to his favorite son and intended successor, Eric Bloodaxe (Eiríkr Blóđřx), who ruled alongside him for three more years until his death

in approximately 933.

After his father's death Eric had four of his brothers killed, which may be the source of his nickname. He was a despotic ruler (and his wife, Gunnhild, had

the reputation of a witch), and when his youngest brother, Hĺkon the fosterson of Ćţelstan (Hákon Ađalsteinsfóstri), returned from England with ships and men

provided by his foster-father so he could contest his brother's rule, the Norwegian nobles readily gave him their support in ousting Eric in 934. (Eric made

several attempts to regain the throne, then moved to the Orkney Islands and later to the Kingdom of Jorvik (York). He was initially welcomed by Ćţelstan, who

appointed him ruler in Northumbria with the job of defending against Scottish and Irish raiders. But he rapidly became unpopular there, was expelled by the

populace and betrayed by Earl Osulf of Bernicia to one Earl Maccus, and in 954 was killed in the Battle of Stainmore along with his son, Hćric.)

King Hĺkan is also called "the Good." He had to beat back challenges from Eric's other sons and was mortally wounded at the Battle of Fitjar in 961, after

a final victory over them. He had been baptized in England and was the first Xian king of Norway. This caused friction with the conservative nobles, but he

did not attempt to force his subjects to convert and introducing Xianity can be said to have been the only thing he failed at. In fact his court poet, Eyvindr

Skáldaspillir, ignored it when he died and composed a memorial poem, Hákonarmál, in which he is welcomed by the gods into Valhalla.

Despite their defeat at Fitjar, the Ericssons took over the country, led by Harald II (Haraldr Gráfeldr, Harald Greycloak or Greyhide), but they had little

power outside the west. Harald attempted to strengthen his rule by killing the local rulers Sigurd Hĺkonsson, Tryggve Olafsson and Gudrřd Bjřrnsson. He also

undertook a viking expedition to Bjarmaland in northern Russia. In 971, he was tricked into going to Denmark and killed in a plot planned by Sigurd Hĺkonsson's

son Hĺkon Sigurdsson, who had become an ally of the King of Denmark, Harald Bluetooth.

Hĺkon was one of the "Hlađir jarls" (earls of Lade, in eastern Trřndelag), a dynasty of nobles whose fates had become intertwined with the kings'. His

father Sigurd had been an adviser to Hĺkon the Good, and was killed by Eric; Sigurd's father Hákon Grjótgarđsson had been an ally of Harald Fairhair in his

unification enterprise. Hĺkon ruled as king in all but name. At first he was a loyal vassal of Harald Bluetooth: he obediently attacked Götaland and killed

its ruler Jarl Ottar. But he was a devout heathen, famous for restoring royal sponsorship of the vés and establishing a hof with a massive gold ring on the

door; so around 975, when Harald attempted to force him to convert to Xianity, he broke away. Harald sent a Danish fleet to invade Norway, which was defeated

at the battle of Hjörungavágr in 986. But in 995, a quarrel broke out between Hĺkon and the Trřnders just as Olaf Tryggvason (Óláfr Tryggvason), a descendant

of Harald Fairhair, arrived. Hĺkon quickly lost all support, and was killed by his own slave and friend, Tormod Kark, while hiding with him in the pigsty at

the farm Rimul in Melhus. His two sons Eric and Sven, and several others, fled to the king of Sweden, Olof Skötkonung (whose nickname, "tribute king," may

refer to his close relationship with the Danish king, or to his being the first King of Sweden to mint coins).

If the sagas are telling the truth, Olaf Tryggvason had a difficult childhood. He was supposedly born shortly after his father's death, and his mother fled

two or three times with him; at the age of three he was captured by Estonian pirates and sold as a slave twice, the first time with another boy for a stout and

a good ram, the second time alone for a cloak. His mother's brother chanced to come upon him in Estonia, bought him and took him to Novgorod, where Valdemar

sheltered him but was discomfited when he happened to run into his enslaver and killed him with an axe, and then when he became a rather too popular chief of

his men-at-arms. So Olaf lost his friendship and decided to return to the Baltic. He became a raider and married a queen of the Wends, so he was part of the

Holy Roman Emperor Otto III's great army of Saxons, Franks, Frisians, and Wends that attacked the heathen Danes. Hĺkon Jarl, as Harald Bluetooth's ally, was

fighting for Denmark. Otto's army was unable to break through the Dannevirke, so he sailed around it and landed in Jutland with a large fleet. In this version

of the story, after winning the ensuing battle, Otto forced Harald and Hĺkon with their armies to convert to Xianity; Harald held on to his new faith, but

Hĺkon reneged as soon as he returned to Norway.

Olaf himself was still heathen, but his wife died; shaken, he resumed raiding, and eventually, on one of the Scilly Isles, consulted a hermit who warned him

that an attempt would soon be made on his life and would almost succeed; on recovering, he allowed the hermit to baptize him, and he never again raided

England. In 988 he married again, to Gyđa, the daughter of the King of Dublin, Amlaíb Cuarán or Óláfr Kváran. They divided their time between Ireland and

England. In 995, rumors started to swirl in Norway about a Norwegian king in Ireland. Hĺkon Jarl successfully lured Olaf to Norway by having one of his men

tell him that Hĺkon had become unpopular because he overused his droit de seigneur and weakened because Harald Bluetooth kept attacking him over Xianity.

Unfortunately for Hĺkon, when Olaf did arrive, instead of being where Hĺkon could keep an eye on him, he rapidly caused Hĺkon's own death.

Olaf set up his seat of government in Nidaros (now Trondheim), where he had first held thing with the rebels against Hĺkon. It was a good site because the

River Nid made a loop around a peninsula that could be easily defended against land attacks.

Olaf was a determined, often brutal converter. One of his first acts as king was to travel to the parts of Norway that had not been under Hĺkon's rule, but

Harald of Denmark's; when they greeted him rudely, he demanded that they all be baptized and those who did not he had tortured or killed. He converted the

Orkney Islands, then part of Norway. He had spćmenn bound and left on a skerry at ebb tide, and listened to their shrieks as the water rose and drowned them.

He tried to marry Sigrid the Haughty, queen of Sweden, but instead made an enemy of her by insulting her for being heathen, so instead he made a further

enemy by marrying the sister of King Sweyn I (Forkbeard) of Denmark, Thyre, who had fled from her heathen husband Burislav (Mieszko I) in defiance of her

brother's authority. In 1000, on an expedition to get back her lands from Burislav, he was waylaid off the island of Svolder by the combined Swedish, Danish,

and Wendish fleets, together with the ships of Earl Hĺkon's sons. Olaf fought to the last on his great vessel the "Long Serpent" (Ormurin Langi), the mightiest

ship in the North, and finally leaped overboard and drowned himself.

The effect of Olaf's zeal was therefore to return Norway to rule by a jarl under foreign control - this time in fact three jarls and the kings of both

Denmark and Sweden, but chiefly Hĺkon's son Eric (Eiríkr Hákonarson) under Sweyn Forkbeard's control. According to the sagas, Hĺkon had conceived Eric on a

fling with a woman of low birth, did not like the boy, and sent him away to be fostered. When he was eleven or twelve years old, his father's best friend,

Skopti, ordered him and his fosterfather to move their ship out of the way so he could park his next to the jarl's as usual; the boy hunted him down and killed

him. He then sailed south to Denmark, where King Harald Bluetooth did like him, and after he passed the winter with him, made him Jarl of Romerike and

Vingulmark, two southern Norwegian districts long under Danish influence.

If the sagas are to be believed, soon after that he was reconciled with his father against Harald, since they have him commanding 60 ships in the Battle

of Hjörungavágr, in which a Danish invasion fleet - and the Jómsvikings - were repelled.

When Olaf Tryggvason seized power in Norway, Eric was forced into exile in Sweden, where he allied himself with King Olof of Sweden and King Sweyn

Forkbeard of Denmark, whose daughter, Gyđa, he married. Using Sweden as his base, he launched a series of raiding expeditions into the east.

He played a heroic part in the Battle of Svolder and took possession of the Long Serpent and steered it home.

From 1000 to 1012 Eric governed a large part of Norway under Sweyn Forkbeard while his brother Sveinn Hákonarson governed a smaller part under Olof the

Swede; then Eric's son Hĺkon (Hákon Eiríksson) governed under Sweyn until 1015. Eric and Sveinn consolidated their rule by marrying their sister Bergljót to

Einarr Ţambarskelfir, a powerful relative of theirs who had been a prominent supporter of King Olaf at Svolder, thus gaining a valuable advisor and ally.

Their rule was generally peaceful; Eric forbade duelling and exiled berserks shortly before his expedition to England.

Supposedly Eric had oathed to convert to Xianity if victorious at Svolder, and both he and his brother did convert, but were taken to task for not forcing

it on people as Olaf had done. It may have been a move of political expediency: they were allied with the Xian rulers of Sweden and Denmark. The court poetry

of Eric's time is conventionally heathen. Or they may have simply shared Harald the Good's philosophy of tolerance.

In 1014 or 1015 Eric left Norway and joined Sweyn Forkbeard's son Cnut (Knútr, known in England as Canute), then still young and inexperienced, for his

campaign in England. In midsummer 1015 the Scandinavian invasion fleet landed at Sandwich, where it met little resistance. Cnut's forces moved into Wessex and

plundered in Dorset, Wiltshire and Somerset. Alderman Eadric Streona assembled an English force of 40 ships and submitted to Cnut. In early 1016 the army

crossed the Thames into Mercia, plundering as it went. Prince Edmund attempted to muster an army to resist the invasion but did not succeed, and Cnut's forces

continued unhindered into Northumbria, where Uhtred the Bold, Earl of Northumbria, was murdered. Cnut gave Eric the earldom. After conquering Northumbria the

invading army turned south again towards London. Before they arrived King Eţelred the Unready died (on April 23) and Prince Edmund (Ironside) was chosen king.

The Scandinavian forces then besieged London, possibly under Eric's leadership. After several battles Cnut and Edmund reached an agreement to divide the

kingdom, but Edmund died a few months later, and in 1017 Cnut became undisputed king of all England. He divided the kingdom into four parts: Wessex he kept for

himself, East Anglia he gave to Thorkell, Northumbria to Eric, and Mercia to Eadric. Later the same year Cnut had Eadric executed as a traitor.

Eric remained as Earl of Northumbria until his death. His earlship is primarily notable in that he is never recorded as fighting with the Scots or the

Britons of Strathclyde, who were usually threatening Northumbria. Eric is not mentioned in English documents after 1023. According to English sources, he was

exiled by Cnut and returned to Norway, but there are no Norse records of his supposed return. Eric's successor, Siward, cannot be confirmed as being Earl of

Northumbria until 1033 so all we know is that Eric died between 1023 and 1033. According to the Norse sources he died of a hemorrhage after having his uvula

cut (a procedure in medieval medicine) either just before or just after a pilgrimage to Rome.

In 1015, Olaf Haraldsson (known in his lifetime as Olaf the Fat; he later became St. Olaf) arrived in Norway from England and Hĺkon Eiriksson fled to

England, where Cnut made him Earl of Worcester. Olaf declared himself King Olaf II, obtaining the support of the five petty kings of the Uplands, and in 1016

defeated Earl Sweyn, Eric's brother, at the Battle of Nesjar. He founded the town Borg by the waterfall Sarpr, later to be known as Sarpsborg.

Within a few years he had won more power than had been enjoyed by any of his predecessors on the throne. He had annihilated the petty kings of the South,

crushed the aristocracy, enforced the acceptance of Christianity throughout the kingdom, asserted his suzerainty in the Orkney Islands, conducted a successful

raid on Denmark, achieved peace with King Olof Skötkonung of Sweden through Ţorgnýr the Lawspeaker, and was for some time engaged to his daughter Ingegerd

Olofsdotter without his approval. (After the end of her engagement to Olaf, Ingegerd married the Great Prince Yaroslav I of Kiev.) In 1019 Olaf instead married

Olof's illegitimate daughter Astrid. They had only a daughter, Wulfhild, who he married in 1042 to Duke Ordulf of Saxony.

But Olaf's success was short-lived. In 1026, he and the Swedes lost the Battle of the Helgeĺ against Cnut the Great's navy, and in 1029 the Norwegian

nobles, seething with discontent, rallied round the invading Cnut, and Olaf had to flee to Kievan Rus. During the voyage he stayed some time in Sweden in the

province of Nerike, where according to local legend he baptized many locals. Cnut restored Hĺkon Eiriksson as vassal ruler of Norway, but he was lost at sea

in 1029 or 1030. Olaf in turn sought to return, but his own subjects again opposed him and he was killed at the Battle of Stiklestad (Stiklarstađir): his 3,600

men opposed by a peasant army 7,000 strong, led by Hĺrek from Tjřtta (Hárekr ór Ţjóttu), Tore Hund (Ţórir Hundr), and Kalf Arnason (Kálfr Árnason), a man who

had previously served him.

Olaf II was probably the first king of Norway to extend his rule to the inland regions of eastern Norway and to rule more or less the whole of the

present-day country. He was also at least as brutal as Olaf Tryggvason in forcing people to convert: it was the second Olaf who had Rauđr the Strong murdered

for refusing by inserting a horn into his mouth with a poisonous snake in it and heating it so that the snake slithered down his throat.

Some Xians at least appreciated his talents: he was soon hailed as a martyr and was canonized in 1164 by Pope Alexander III. By the end of the 11th century,

Xianity was the only religion allowed in Norway, and St. Olaf is now the country's patron saint. In theory, later kings of Norway were said to hold the kingdom

as his vassals.

After his death, Norway was ruled from Denmark as part of Cnut the Great's "North Sea Empire."

In 1035, Olaf's illegitimate son Magnus I (Magnus the Good) took the throne, and in 1042 also became king of Denmark.

Magnus was succeeded by the youngest of the illegitimate half-brothers of Olaf II, Harald III, known as Harald Hardrada (Haraldr Harđráđi, "Hard-Ruler") and

as "the last of the vikings." Haraldr had been wounded at Stiklestad, but escaped and went east with some followers and entered the service of Yaroslav I the

Wise, the Grand Prince of the Kievan Rus, becoming joint commander of his defense forces. After a few years he and about 500 followers then went to

Constantinople and joined the Varangian Guard, an elite mercenary unit of Norsemen in the service of the Byzantine Emperor. Harald was so successful in battle

that he became the commander of the Guard and used it as his private army to conduct raiding campaigns in North Africa, Syria, and Sicily. They were extremely

lucrative, partly because of Harald's ingenuity in cracking castles, for example tying burning material to birds' feet and launching them over the walls. He

also won fame for destroying the uprising in which Peter Delyan attempted to restore the Bulgarian Empire. There is a theory that he renamed Oslo (previously

known simply as Vík, "Bay") after a Bulgarian woman named Oslava. Heimskringla also has him conquering Jerusalem, undergoing baptism in the Jordan, and making

the city safe for pilgrims by eliminating thieves from the roads leading to it, stealing the thunder of the later Crusader kings of Jerusalem, but this could

be pro-Norwegian monarchical hagiography on Snorri Sturluson's part. He returned to Norway in 1045 on hearing that his nephew had become king; with all his

booty he was a considerable threat to Magnus, who wisely offered to share the throne with him in 1046; within a year he was dead (possibly with Harald's

assistance) and in 1047 Harald became sole king. Until 1064 he continued to rule Denmark as well, several times defeating King Sweyn and forcing him to leave

the country. In 1066 he invaded England and was killed by King Harold's forces at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, which is generally considered the end of the

Viking Age. He had won an initial victory at Fulford and had his forces only lightly armed; of the 300 longships that had brought his invasion force over,

only 25 were needed to transport the survivors home.

Harald Hardrada was succeeded by his sons Magnus II and Olaf Kyrre ("the Silent"), who divided the kingdom between them like any other property, a pattern

which was to continue and cause confusion in succession. In 1069 Magnus died, apparently of ergot poisoning, leaving Olaf to reign alone. Olaf made peace with

William the Conqueror of England and with Svend Estridsen of Denmark, who held a claim to the throne and whose daughter Ingerid he married. He improved

relations with the Pope. He instituted the system of guilds and continued the strengthening of the power of the king. It was probably during his reign that the

oldest recorded law of Norway, the Gulaţingslög, was first written down. He himself learned how to read and write, the first Norwegian king to do so. And in

1070 he founded the city of Bergen.

When Olaf died in 1093 the problem of succession reared its head: his brother Magnus' son Hĺkon Magnusson was hailed as king in Trondheim, while his

illegitimate son Magnus Berrfřtt was hailed as king in Viken. The two cousins seemed headed inevitably for war when Hĺkon suddenly died during a trip over

Dovrefjell in 1094. Magnus (called "barefoot" either because he liked to wear Celtic-style garb, barelegged under a tunic, or because he once had to flee from

a battle in his bare feet) was a stark contrast to his peacemaking father. He made war with Sweden and Denmark and sought to build a Norwegian empire around

the Irish Sea. In 1098, he conquered the Orkney Islands, the Hebrides, and the Isle of Man. He returned to Norway in 1099 but in 1102 set out again, this time

to conquer Ireland. He captured Dublin and the surrounding area, but the next year, 1103, when he sought to broaden his conquest to the whole of Ireland, he

was caught in an ambush and killed.

Upon Magnus' death he had three known sons, Olaf Magnusson, Řystein Magnusson, and Sigurd Magnusson (later known as Sigurd Jorsalfar or "the Crusader") who

all together succeeded him. Two additional claimants came forward saying they were his illegitimate sons and thus likewise heirs: Harald Gille and Sigurd

Slembedjakn. Olaf Magnusson fell ill and died at 16 in 1115; he does not even have a number as a King Olaf. Řystein and Sigurd ruled together until Řystein

died in 1123; not in perfect equanimity, but Řystein focused on internal governance and Sigurd on external, Řystein in particular holding the fort while his

brother was on crusade from 1107 to 1111 (the first European king to go). After returning to Norway, Sigurd made his capital in Konghelle (now Kungälv in

Sweden) and built a castle there where he kept a relic given to him by King Baldwin, a splinter reputed to be from the True Cross. In 1123 Sigurd once again

set out to fight in the name of the church, this time to Smĺland in Sweden, where the inhabitants had backslid into heathenry. Sigurd also benefited the church

by introducing the tithe. On the other hand, he founded the diocese of Stavanger just so he could get a divorce after the Bishop of Bergen told him no.

After Sigurd's death in 1130, the succession broke down completely and an era of civil war began that was to last until 1217 or 1240.

Sigurd and his queen Malmfred had a daughter, Kristin Sigurddatter, but no legitimate sons. There were also the two who had claimed to be his father's

illegitimate sons in 1103.

Initially an illegitimate son of Sigurd, Magnus IV, became king together with one of the 1103 claimants, Harald Gille as King Harald IV. But after four

years of uneasy peace, Magnus began to openly prepare for war on Harald. On August 9, 1134, he defeated Harald in a decisive battle at Färlev in Bohuslän,

and Harald fled to Denmark. Against the advice of his councillors, Magnus disbanded his army and went to Bergen to spend the winter. Harald returned to Norway

with a new army and, meeting little opposition, reached Bergen by Xmas. Magnus had few men, and the city fell easily to Harald's army on January 7, 1135.

Magnus was captured and dethroned. He was blinded, castrated and had one leg cut off. After this he was known as "Magnus the Blind." Magnus then entered a

monastery. Harald Gille was killed in 1136 by Sigurd Slembe, another royal pretender who had himself proclaimed king in 1135. To back his claim, Sigurd Slembe

brought Magnus back and made him co-king. They decided to split up their forces, and Magnus headed for eastern Norway, where he had most popular support.

There, he was defeated at Minne by King Inge I, yet another simultaneous king of Norway. He fled to Götaland and subsequently to Denmark, where he tried to

get support for his cause. An attempted invasion of Norway by King Erik Emune of Denmark failed miserably. Magnus then rejoined Sigurd Slembe's men, but they

continued to have little support in Norway. After some time spent more like bandits than kings, they met King Inge I and King Sigurd II in a final battle at

Hvaler on November 12, 1139. Magnus fell during the battle (a loyal follower, Reidar Grjotgardsson, held him up and they were both run through by the same

thrown spear), and Sigurd Slembe was captured and killed.

This chaos continued not only because there were so many potential claimants to the throne but because of political conflicts between nobles and because of

the emergence of two loose parties or sides that came to be called the Birkebeiner and the Bagler. The Birkebeiner ("birch-legs") were mockingly called that

because they were so poor they had to lash birchbark to their legs for want of breeches. Eventually they adopted the term as a point of pride, even after

they came to power. One impetus to the growth of their party was the rapid increase in landless markamenn ("border men") who settled along the Swedish border

and made their living by pillaging the rich old settlements. The opposing faction, the Bagler, was made up of aristocrats, clergy, and merchants, basically

reactionaries. But there was also a geographic element: the center of Birkebeiner power was the Trřndelag, while the Bagler faction began in Skĺne.

This long struggle came to a heroic and triumphant end. In 1204, Inga of Varteig gave birth to a baby whom she called Hĺkon and claimed was the illegitimate

son of Hĺkon III of Norway, a Birkebeiner king who had visited Varteig, in what is now Řstfold, the previous year and subsequently died. He had been attempting

to make peace with the Bagler and poisoning was suspected. The child was born in Bagler-controlled territory and his mother's claim that he was a Birkebeiner

royal son placed them both in a very dangerous position. In 1206 the Bagler started hunting Hĺkon and a group of Birkebeiner warriors fled with the baby boy,

heading for King Inge II of Norway, the Birkebeiner king in Nidaros (now Trondheim). On their way they found themselves in a blizzard, and only the two

mightiest warriors, Torstein Skevla and Skjervald Skrukka, continued on skis, carrying the child in their arms. They managed to bring him to safety and after

King Inge's death in 1217, at the age of 13, he was chosen king. Hĺkon IV reigned until 1263 and came to be called Hĺkon the Old; it took a while and some

surprising twists and turns (including Inga surviving an ordeal to prove she was telling the truth about her son's parentage, the church reversing its now

stricter policy on illegitimacy to crown him, and intrigues about annexing Iceland in which Snorri Sturluson was on the king's side and that brought about his

death), but his reign brought the civil war to an end and saw Norway achieve its greatest flowering of the Middle Ages.

Norway's most important annual skiing event, the Birkebeiner ski race, and the American race derived from it commemorate this deed of heroism and toughness.

[1. Norway 930 CE map image from http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/85/Norwegian_petty_kingdoms_ca._930.png]